Zoom in on others’ mistakes – Vol.1: Injection

In this first article we'll analyze the injection vulnerabilities that have put Zoom in the software security crossfire.

Zoom attracted remarkable attention in the last weeks. Not only because a massive amount of people who started to work from home, but also because of several vulnerabilities revealed recently. The two circumstances are of course not completely independent. The popularity of a product always attracts hackers, ethical or not, posing a challenge to software security.

And it’s not only about popularity. Governments and agencies started to use online video conferencing tools as well, and that made these products even more sensitive from a confidentiality perspective. The situation is even more embarrassing due to continuous marketing communication done by Zoom in the past. They emphasized end-to-end encryption as a software security feature – and this appeared to be misleading.

There have been only a few CVE entries for Zoom so far, but that is likely to change soon. While some of the recent stories may be just fuss and FUD, there are also many serious issues amongst the new findings. We’ll take a closer look to them, strictly from software security standpoint. It’s always good to learn from other peoples’ mistakes, isn’t it?

In this article we’ll look at the injection flaws. You can read about further vulnerabilities in Zoom in the next article that deals with the cryptographic weaknesses.

From injection in Zoom to stealing Windows credentials

Injection problems are on the top of the OWASP Top Ten for more than a decade now, and are not likely to disappear from there any time soon. Thus, it is not surprising that one of the recent problems in Zoom is an injection flaw. The silver lining is that it only affects Windows clients: it’s all about the (mis)handling of UNC (Universal Naming Convention), the well-known resource address that start with a double backlash.

Zoom turned any sent URLs into hyperlinks, which is OK from the user experience perspective. However, the chat windows also did this for UNC strings, making them clickable links as well. The problem – as revealed by a researcher – was that when clicking on a UNC link, Windows used the SMB protocol (remember WannaCry?) that sent along the username and the hashed NTLM password of the current Windows user. It was “just” a hash of course, and not the plaintext password; but this obviously is a vulnerability. A weak password – once learnt by an adversary – can be easily brute forced and cracked just within minutes with an appropriate tool and enough processing power.

A side note for DevOps: automatic sending of NTLM credentials when using a UNC link can be switched off in a Group Policy by setting Outgoing NTLM traffic to remote servers to Deny all. Similarly, on Windows 10 Home there is a registry entry for the same purpose: just set the RestrictSendingNTLMTraffic key to 2 under HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Lsa\MSV1_0.

Remote command execution

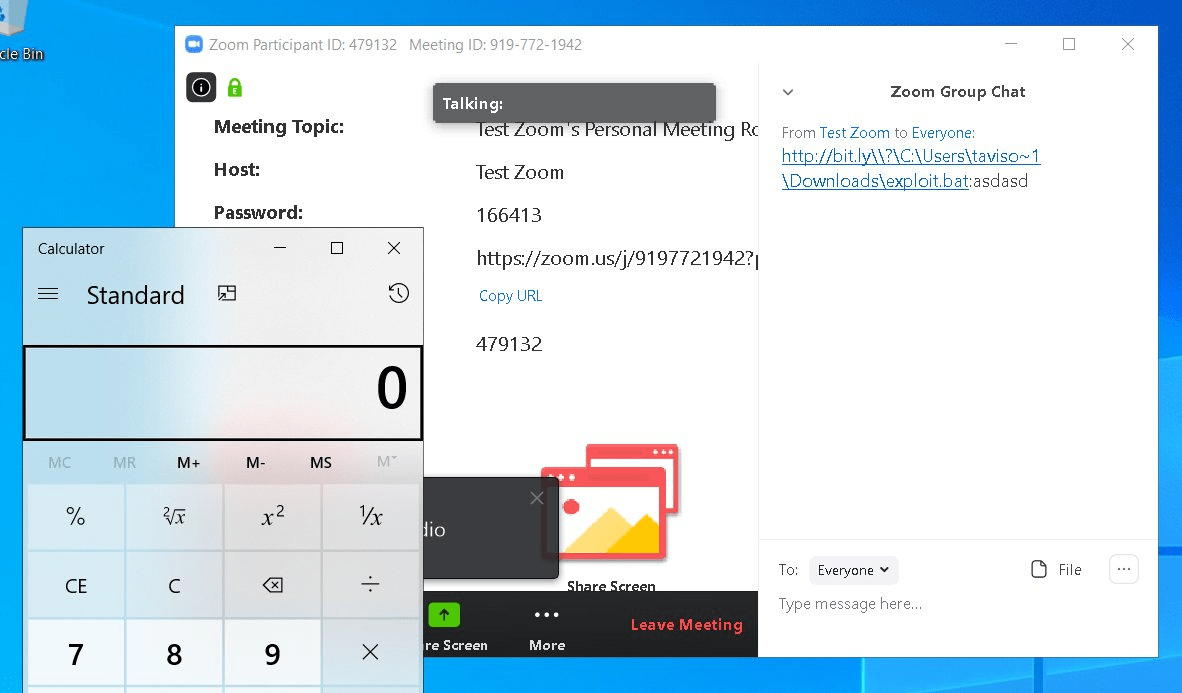

Even worse – as shown by another researcher – a careless Zoom user can be easily fooled to execute arbitrary commands on their computers just by clicking a link. Clickable UNCs could point to executable files as well; thankfully, if the address pointed to the Web, it had a Mark of the Web indication on it, and so Windows displayed a prompt first that asked the user if they really wanted to run this executable. The bad news is, however, that if the UNC points to a local file (e.g. \\?\C:\Windows\System32\calc.exe), it will be executed silently, without displaying any dialogs, user prompts, or warnings. Note the \\?\ at the beginning: it indicates that the rest of the UNC is a path on the local file system.

Based on Tavis Ormandy (@taviso on Twitter)

This is obviously a command injection possibility, but we should note that the associated risk is somewhat lower than that of command injection in general. The victim needs to click on a link in Zoom chat to execute the malicious command. Nevertheless, the likelihood of this is still not negligible, and the consequences may be disastrous.

Lessons learnt

Injection is a low-hanging fruit among the contemporary vulnerabilities. Being a medalist on the OWASP Top Ten for a decade now, it should be given continuous attention; even SQL injection remains a constant concern despite entering public knowledge over the last 10 years. Obviously, Zoom developers were unaware of this essential software security weakness. Neither did they follow some general input validation and UI design principles and best practices.

The specific behavior of SMB related to UNCs reveals another common issue. When using a component from the environment or a third-party solution, one should always be fully aware of all details. For example, sending NTLM credentials along with the request is not a bug, it’s a feature; however, not knowing about it may leave applications vulnerable, just as it happened in this case.

The above vulnerabilities, as well as Zoom’s approach in general are also a good example for a simple rule of thumb: usability and security are usually at odds with each other. Whenever you focus on one, you lose something from the other; and it’s always hard to find the right balance between the two.

Finally, note that Zoom has already fixed the above problems. The newest version (released early April 2020) does not turn URLs or UNCs to hyperlinks anymore. They have also announced full transparency and a 90-day feature freeze to give more focus on security and privacy issues.

Injection is a critical vulnerability type that’s unlikely to go away anytime soon – and we give it the attention it deserves in our material. Whether your application is written in C/C++, C#, Java or Python, we cover it all from the well-known (SQL injection, OS command injection, HTML injection aka cross-site scripting) to the technology-specific (Javascript injection, XML injection, JSON injection) and OS-specific subtypes (library injection). We also cover less-known but just as important injection types, such as SSTI (server-side template injection) and expression language injection. Learn more about injections by perusing our course catalog!