OWASP Top 10 2025: is it really just ‘more of the same’?

The OWASP Top 10 2025 is out, and it does not bring any big changes to shake things up this time... or does it?

The final version of the OWASP Top 10 2025 has just been released, and unlike the significant changes between 2017 and 2021 (see an analysis here), this update represents more of an evolution than a revolution. This isn’t a bad thing, of course – if anything, it shows that even major technological shifts don’t necessarily induce new types of issues, so we can continue using our existing categories and expertise to address them.

The Top 10 is probably the single best-recognized document in the world when it comes to software security. The list is published and regularly updated by OWASP, i.e. the Open Worldwide (formerly: Web) Application Security Project community. It all started in 2003 as a list of the most critical web application vulnerabilities, helping developers focus on the highest-risk issues. Over time, it gradually evolved from a list of specific problems like buffer overflow or cross-site scripting to covering a broader category of issues, like design flaws, misconfigurations or authentication. It’s becoming comprehensive, more a “list of everything” rather than a top ten driving the focus. But that’s also OK.

An interesting observation is that while originally the policy was to update the list every three years, the release cycles have been de facto four years in the last couple of releases. OWASP never communicated any change in this, but the community already started to refer to the cycles as “every 3 or 4 years”.

OWASP hasn’t changed the methodology significantly either (see here for some details), but, again, there are some important nuances. Instead of picking 8 categories based on the reported CWE data (objective) and 2 CWEs from community input (subjective), OWASP now selects 12 categories based on the data, and asks the community to highlight two of them. The 10 highest-risk categories are elevated to the actual Top 10, with the exception that if a category is highlighted, it must be included in the Top 10 even if the statistics don’t support it. Just as before, this helps put issues on the radar that are serious even if they’re not easily identifiable from the data, or issues that may not look important or critical now but are expected to become significant over the next few years. The remaining two categories that don’t make it become Next Steps. Some issues can belong to multiple categories at the same time (this is also acknowledged by the authors).

Meet the new Top 10

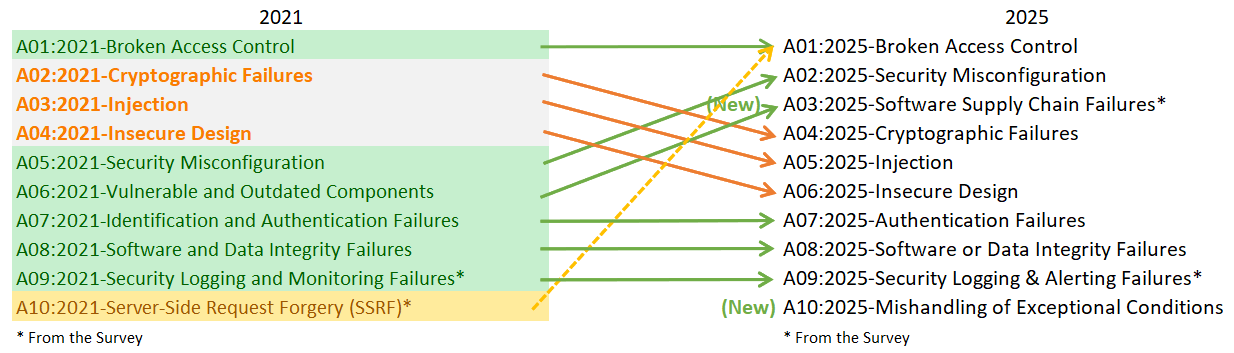

Let’s look at the new OWASP Top 10 2025 through the mapping image from the document – if we wanted to summarize it, the only major change is that DevSecOps seems more important than ever. Specifically:

Source: OWASP.ORG

- A01:2025 is Broken Access Control. The golden medalist for the second time now, with some minor tweaks. Server-side request forgery aka SSRF has been merged into this category now, as a confused deputy issue – which also means that there are no ‘single-vulnerability’ OWASP Top 10 entries anymore, every item encompasses multiple vulnerabilities. Otherwise, A01 is largely unchanged and remains the most significant issue overall. An interesting question concerns the relationship between “access control” and “authorization”: in the view of many – one we also share –, access control encompasses authentication and authorization (among other aspects; in any case, it’s a core component of it). OWASP, however, clearly treats the two as synonyms: A01 focuses on authorization (having access control in the title), while authentication is addressed separately in A07.

- A02:2025 is Security Misconfiguration. The category hasn’t changed much, but it moved from #5 to #2 – these issues became much more relevant with higher and higher reliance on configurable components, containers and cloud services – and DevSecOps expectations – because sometimes all it takes is forgetting to change the default “admin/adminadmin” credentials in a single component somewhere.

- A03:2025 is Software Supply Chain Failures. At first, this looks like a rename of Vulnerable and Outdated Components from 2021, but it has climbed the list from #6 to #3 due to its very high incidence rate. The item is also one of the two that got highlights by the community. Issues now encompass attacks targeting external systems like artifact repositories as well as dependency ecosystems. This is much more about failures in enforcing consistency when it comes to updates and configuration on the management and infrastructure level – specific concerns about the integrity of code and package managers are discussed in A08 instead. It also mentions a new practice to mitigate this issue: Software Bill of Materials aka SBOM, which can be implemented via the OWASP CycloneDX standard. Fail to check the integrity of your build system and you can end up with SolarWinds-level compromise of an entire country’s cyber infrastructure.

- A04:2025 is Cryptographic Failures. This issue remains the same as it was in 2021, but has dropped two positions from #2 to #4 in the OWASP Top 10 2025, outscaled by the high-incidence “DevOps-focused” issues. Interestingly, the most observed issues are related to improper use of pseudo-random number generators (PRNGs) rather than incorrect use of encryption. This makes sense considering random and cryptographically secure random number generation tends to be separate in most languages, and many developers may not know the difference – for example, the session token used by older versions of the OpenVPN Access Server was potentially predictable due to weak PRNG. With NIST releasing quantum-safe algorithms (using lattice-based cryptography and stateless hashes), the adoption of post-quantum cryptography is now also on the radar with a soft deadline of 2030.

- A05:2025 is Injection. As a longtime front-runner of the Top 10, seeing this drop from #3 even further to #5 is hopefully an indicator of positive changes in the developer community – that is, frameworks trying to prevent developers from shooting themselves in the foot. But ultimately, injection vulnerabilities are introduced by developers failing to perform proper processing (validation and sanitization) of user input and are not going away anytime soon. And sometimes an attacker may just exploit a SQL injection to bypass airport security checks.

- A06:2025 is Insecure Design. Together with the previous two categories, this has dropped from #4 to #6. Following the discourse around the 2021 list, this category now more explicitly focuses on integrating security into the SDLC via the OWASP Software Assurance Maturity Model (SAMM) and it emphasizes threat modeling as an activity developers should get familiar with.

- A07:2025 is Authentication Failures. This remains the same with a shortened name – and kept its position, showing that many of the issues in this category won’t go away. Even as web application frameworks improve, they can’t prevent a developer from using hardcoded passwords, creating a weak password policy, checking the wrong claims in JWTs, or forgetting to invalidate session data after login. Storing passwords with the right algorithm technically belongs to A04 as well as this category.

- A08:2025 is Software or Data Integrity Failures. The only minor change for this category was the name (“software AND data” became “software OR data”) to better emphasize that it can refer to both. Though the category hasn’t changed, the threats have definitely shifted – for instance, with a surge in AI/ML products, the wild insecurity of model deserialization came to the fore, potentially turning any model downloaded from the web into a remote code execution vector (see e.g. Models are Code).

- A09:2025 is Security Logging & Alerting Failures. The only change was, again, a minor clarification of the name (“monitoring” has been changed to “alerting”). This remains the other community-voted issue due to lack of viable representation in test data. Injection attacks against log files (just think of Log4Shell for an extreme example why putting user input into log files without any validation can be dangerous) sound like they’d belong to A05 (as well), but nonetheless OWASP placed them here.

- A10:2025 is Mishandling of Exceptional Conditions. This new category is actually a distillation of what used to be in the Next Steps section earlier (A11:2021). As part of code quality, it is about handling errors and exceptions correctly, but at a higher level it is basically about always expecting that input may be incorrect, and the code needs to be robust enough to account for that. Instead of failing functionally, the new paradigm is failing safely and securely. This encompasses issues like releasing resources after using them, exposing sensitive information via error messages, and malfunctioning when a multi-step transaction is intentionally corrupted and performed in the wrong order.

Speaking of the Next Steps: these are the three broad categories of issues that were being considered for inclusion but didn’t make it to the top ten list. Make no mistake – these threats did not disappear, they remain lurking beneath the surface, ready to cause significant damage if ignored!

- X01:2025 is Lack of Application Resilience. This was previously known as Denial of Service, and it encompasses any kind of problem that can damage the system’s availability and can be triggered intentionally by malicious actors. These vulnerabilities are still caused by programming mistakes such as an infinite loop, endless resource consumption, performance bottlenecks or algorithmic complexity issues such as Regular Expression Denial of Service (ReDoS). This latter, for instance, affects Node.js particularly severely due to its single-threaded model.

- X02:2025 is Memory Management Failures. A lot of code was (and still is) written in high-performance low-level languages like C/C++, which opens up the possibility of reading or writing to the wrong location in memory via buffer overflow, use after free, and similar vulnerabilities. The consequences can be absolutely devastating, just think of the memory over-read error in CrowdStrike Falcon causing global outage and massive damage. It may look like this is not relevant for web developers working in managed languages, but these vulnerabilities can pop up, for instance, in the browser; or in a subcomponent written in low-level code. The zero-day MongoBleed vulnerability from the end of 2025 was a heap buffer over-read vulnerability that hackers .

- X03:2025 is Inappropriate Trust in AI Generated Code (‘Vibe Coding’). This was an “extra” item in the Next Steps that has been added very late to the Top 10, but it is so important that it deserves a more detailed analysis!

… but what was that about vibe coding?!

First of all, it may sound a bit strange to see three Next Steps categories when the twelve categories imply a maximum of two – and that’s how it was for the release candidate version of the OWASP Top 10 2025. The vibe coding entry was added for the final release (see post-RC1, pre-release commit), but that was a very important call to make. Generative AI for programming is relatively new with lots of uncertainties, but the tools are easy to use and produce results that look (and sometimes run) great. Thus, it’s understandable why so many developers are using it. Sometimes this can even allow fully fire-and-forget agentic operation: the developer gives the AI tool the documentation for the system to implement, and it autonomously creates the runtime environment, writes the code and tests the system itself without any necessary human oversight or understanding about what is actually happening in the process. Andrej Karpathy summarized this as “vibe coding, where you fully give in to the vibes, embrace exponentials, and forget that the code even exists”.

But there is a huge underlying risk: the models driving these systems are trained on real code, and much of that real code was vulnerable in the first place. Consequently, models can and often do generate vulnerable code. To directly quote X03:2025: “[…] Good, secure code snippets were and are rare and might be statistically neglected by AI due to system constraints.”. Generative and agentic AI writing code can make the same mistakes as a human developer, especially when it comes to the Top Ten. Just for some examples that went viral: the experimental vibe-coded MCP OAuth provider of Cloudflare failed to implement an essential check, which allowed attackers to downgrade protocol security by removing PKCE, Sketch caused inadvertent DoS via a vibe-coded infinite loop, there is a persistent issue of AI code tools hallucinating packages and enabling supply chain attacks aka slopsquatting, the list goes on. Blind vibe coding is a sure-fire way to produce code full of vulnerabilities. As we like to say, “it (somehow) works!” is the biggest enemy of security.

Since AI-generated code isn’t clearly marked and attributed, no evidence of this remains when investigating a vulnerability. But regardless, even if the code comes from a generative AI, it is the (human) developers who are still fully responsible for the code they commit to the repository. This makes vibe coding the equivalent of trusting hundreds or thousands of lines of third-party code downloaded from the internet – a very dangerous idea for anything other than a hobby project or some internal prototype! AI should not be used to generate production code by itself – instead, it should be used to write code for well-specified narrow tasks that can then be easily reviewed by the developer as well as (non-AI) security tooling. Only if the code is found to be good (enough), can it be then finally committed to the repository. This topic is widely tackled in our courses as well as a blog post with some of the pain points and possible solutions.

OWASP itself has placed lots of focus on the security of machine learning and generative AI, and the LLM Top 10 has grown into a massive OWASP project on its own over the last few years – this comes as no surprise, considering the significant investment and attention AI is attracting, which in turn draws a large number of supporters and contributors.

It’s (still) not about compliance and rubberstamping

The Top 10 has continued in the direction it took years ago, moving towards a “list of everything” rather than the original “top 10 list of specific vulnerabilities”. This can make it seem less directly applicable as before – for instance, #4 in 2017 was XML External Entities (XXE) which is a single well-defined vulnerability that’s easy to detect, test for, and fix. In both the 2021 and the 2025 Top Ten list, XXE is just one of the issues within Security Misconfiguration. But there is a well justifiable reason for this: 10 concrete issues just meant a one-and-done checklist to go through at some point during development and say “we’re good on security” even though that’s emphatically not the case. There are many more problems, and some of them are deep-seated design issues that cannot be easily described in two sentences and fixed with a single commit. This aligns with a recent trend in OWASP itself: the emergence of more specialized lists that focus on a specific aspect. For example, just between 2021 and 2025, OWASP has released Top 10s for API security, CI/CD security, LLM and GenAI security, mobile security, machine learning security, privacy risks, and many more. Of course, those lists tend to be less mature and don’t necessarily have the rigorous data-driven approach of the “original” OWASP Top 10.

The Top 10 is not (and never has been) a compliance document. Above all, it’s meant as a way to spread awareness and start the security journey. It can also act as a backbone of a thorough secure coding curriculum that is based on the most common and critical vulnerabilities to teach developers how not to code. The Top 10 itself calls this out in multiple places; for instance, Establishing a Modern Application Security Program lays out the basics, and the Next Steps mentions “Take secure coding training that focuses on memory issues and/or your language of choice. Inform your trainer that you are concerned about memory management failures.” and “Train your developers on your policies, as well as safe AI usage and best practices for using AI in software development.”.

Check out our courses to learn more about the ways we can support your generative AI and secure coding initiatives at the same time.