Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF), past and future

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF): an old vulnerability that disappeared from the OWASP Top 10 in 2017. But is it gone?

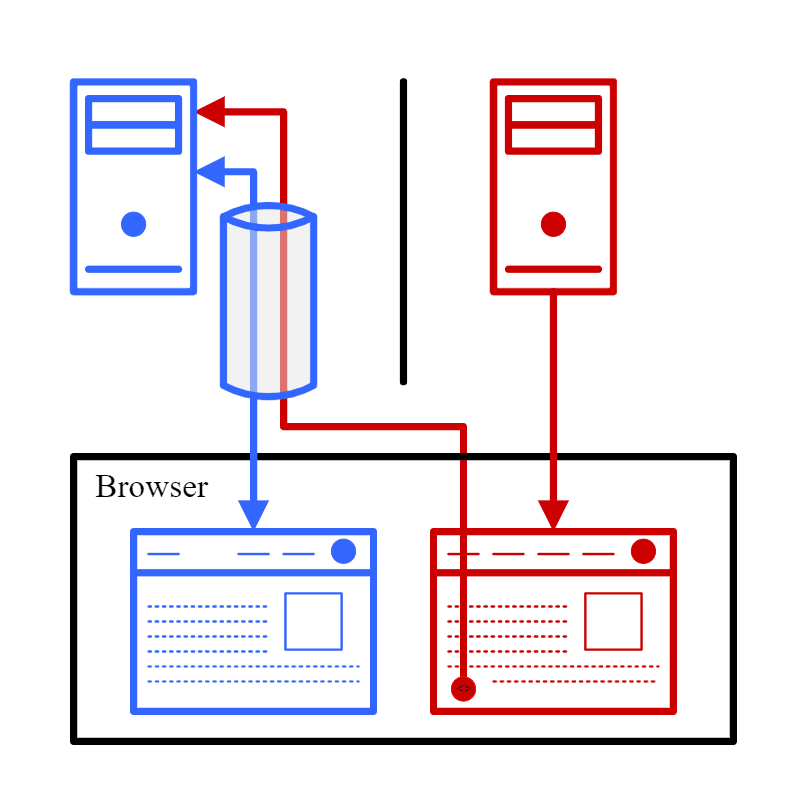

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) tricks the browser into making an authenticated request to a victim site from a malicious site – essentially doing arbitrary actions in the user’s name as long as the user is logged into the victim site. This can be abused to force the user to do actions such as make a purchase, send a message, delete data, log out…

CSRF is a particularly insidious vulnerability, because it exploits the normal operation of Web browsers. They automatically send active session cookies to a website with any request, even if it’s from the context of another page. If browsers didn’t work like this, the user would need to start a new session every time they opened the same site in a new tab in their browser. That would be clearly an unacceptable user experience! Including third-party pages as iframe widgets would be a non-starter as well.

From obscurity to fame to (undeserved?) obscurity

Though CSRF vulnerabilities existed as early as 2000, the term was first defined by Peter Watkins in 2001. The first well-known exploitation was the MySpace worm by Samy Kamkar in 2005 that combined XSS and CSRF to spread. In 2007 it entered the OWASP Top 10 at 5th place, which it maintained in 2010. In 2013, it dropped to 8th place, and finally in 2017 it disappeared from the Top 10 altogether due to an overall low incidence rate as well as many automated solutions built into modern web frameworks.

However, CSRF has recently been in resurgence – according to NVD and CVE statistics, 2.69% of all newly-discovered vulnerabilities in 2018 were classified as CSRF, in the same ballpark as SQL injection (3.02%) and in 2019 the trend seems to continue with CSRF and SQL injection both accounting for around 3.1% of all vulnerabilities.

A token solution

Most CSRF defense mechanisms are still like the recommendations outlined by Watkins in 2001 – generating a single hard-to-guess random value (the token) and sending it to the client, requiring the client to send it back to the server with every request. The two most common protection measures are:

- Synchronizer token pattern: The server generates a strong random session-unique value and includes it as a hidden field in forms as well as custom HTTP headers or possibly URL parameters for AJAX calls, verifying its presence with each request. This is commonly available in web frameworks, usually called ‘CSRF token’ or ‘XSRF token’.

- Encrypted token pattern: The server generates an encrypted token from the session ID and timestamp using a server-only key and inserts it into forms or URL parameters in a similar manner to the synchronizer token, decrypting the user-provided value with each request to verify its presence.

There are also some secondary protection measures – not 100% reliable, but still useful. The most commonly used ones are:

- Double submit cookie pattern: Works just like the synchronizer token pattern but does not require the server to keep track of the token. Instead, the token is sent twice with each request: in the URL as well as the cookie. The server can then compare them.

- Relying on the SameSite cookie attribute: When set to Strict, this attribute tells the browser to only send a cookie to a site if the request is made from the same domain.

Since these solutions can be automated on the web application framework level (e.g. including a CSRF token in every submitted form as well as the URL), mitigating CSRF needs little work from the developer’s side. Still, everyone can make mistakes…

The CSRF of tomorrow

While CSRF seems like a solved problem right now, a very similar attack has emerged with the advent of modern web applications: Clickjacking. Instead of sending a request to the victim page directly, the attacker puts the victim page into an iframe and positions it under the mouse cursor so that when the user clicks somewhere on the attacker page, the click is triggered on an arbitrary location of the victim page instead. The first clickjacking attack was documented by Robert Hansen and Jeremiah Grossman in 2008, and the technique was further refined in 2010 by Paul Stone as ‘Next-generation clickjacking’. This latter version makes use of drag-and-drop tricks to steal or inject data into the victim page in addition to hijacking a click.

See the OWASP Clickjacking Defense Cheat Sheet for protection mechanisms and countermeasures – mainly using the Content Security Policy header, SameSite, and custom JavaScript that prevents the victim page from being visible when it is put in an iframe.

All this shows CSRF is a constantly evolving threat. While it may be absent from the OWASP Top 10 right now, being aware of it – as well as its more modern incarnations such as clickjacking – is essential if you want to protect your web applications!

But don’t worry, we’re here to help. We’re covering both Cross Site Request Forgery and Clickjacking in our Web application security training courses in multiple languages – Python, C# and Java. Check out all our courses related to web application security in our course catalog.