The Twitter hack: just another insider attack?

The 2020 Twitter hack - how social engineering mixed with inappropriate technical protections can cause a disaster.

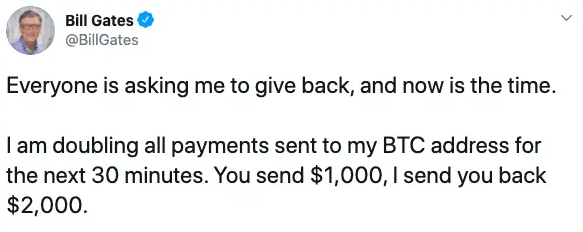

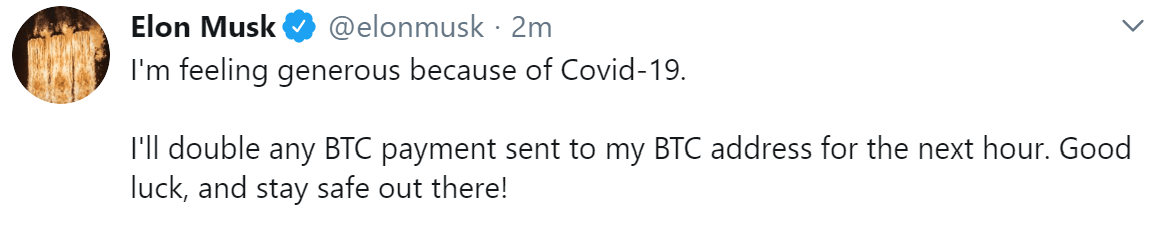

On July 15th 2020, several high-profile Twitter accounts started posting very similar-looking messages, allegedly caused by insiders or a social engineering attack targeting internal employees. Many Twitter accounts were impacted: individuals such as Barack Obama, Bill Gates, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Kanye West and Warren Buffett as well as company accounts such as Uber and Apple. All of these were verified (‘blue checkmark’) accounts with two-factor authentication enabled, and were posted via the official Twitter Web App. The tweets themselves were simplistic cryptocurrency scam attempts – if someone sent some bitcoins to the provided address, they’d of course never get it back.

Twitter’s initial response was to start deleting the fraudulent tweets, but the attackers kept reposting them – eventually the attack was countered by Twitter temporarily making verified members unable to post tweets, and then fixing the underlying problem overnight. But still, for several hours, it was total chaos on Twitter.

What was going on here? How could this happen to Twitter, and – more importantly – can this happen to your products too?

Elon Musk on Twitter: I will double your bitcoins to fight COVID-19!

The scam looks a bit perplexing at first glance. Some of the tweets even referenced COVID-19 as the motivation behind this ‘charity’. Of course, much of the general public does not use cryptocurrencies at all. And those who do probably know better than to get fooled by such an obvious scam.

Impersonating a well-known trusted person on Twitter and promising great return on investment on cryptocurrency is not new – it has been around for years. The FTC specifically mentions it as a common scam type. On the bright side, this meant that some bitcoin wallets blacklisted the address almost immediately after initial reports on the scam, further protecting the users.

That said, the money made from this scam – expected to be on a scale of 100k USD – is not that significant compared to the other ramifications of such an attack. But consider that the attacker was able to essentially hijack the accounts of many powerful people and companies – the potential damage could’ve been much higher. A single fake tweet caused a stock market crash in 2013, after all… Luckily, no harm like that was done this time.

There are a lot of open questions here. Was the attacker just inexperienced and greedy? Was this only a cover for another attack happening in the background (e.g. stealing private messages) and did they do anything else before calling attention to themselves like that? Did the attacker only have a short time window to act? The investigation is still ongoing; it will take some time for the identity of the perpetrator(s) and the technical details of the technique they used to come to the surface.

But let’s focus on the facts. Twitter’s official statement claims that this was the consequence of a coordinated social engineering attack on its employees. This highlights some very common problems in modern software that go beyond Twitter.

“They’re coming outta the walls!”

In general, humans are easier to ‘hack’ than software. There are many social engineering attacks that work surprisingly often. A phishing email, a phone call from an “important client of the company” – with a little bit of research on the victim, attackers can use techniques like these to obtain company secrets from employees. And of course, an employee may just decide to act maliciously on their own for a lot of different reasons. As a consequence of being fired, for instance. In all of these cases, we have an insider attack. The attacker starts with a certain level of access to the system, and usually access to the company’s intranet as well as its internal systems and tools.

Insider attacks are not usually the focus of cyber security discussions, but their danger cannot be ignored. Recent trends in cyber security (e.g. see the 2020 Cost of Insider Threats Global Report by the Ponemon Institute) all show that insider attacks are on the rise – especially the ‘inadvertent’ type as a consequence of social engineering. Some recent high-profile hacks such as Marriott and Capital One also had insider aspects. But just to stay with Twitter:

- Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey’s account was briefly taken over by hackers in 2019 by what’s called a SIM swap attack. Basically, the attackers tricked a mobile operator’s support line to switch Jack’s phone number over to the attacker’s SIM (“I just lost my phone, please switch my number to my new SIM!”). By the way, this attack is a typical way of getting around text message-based two-factor authentication, which is why NIST planned to deprecate it in 2016; they’ve walked it back a bit since then, but they still don’t recommend text messages to be used as the second factor.

- Donald Trump’s own Twitter account was temporarily deactivated in 2017 by a customer support employee on their last day on the job. While that action was easily reversible, it raises questions about how the attackers in this 2020 attack were able to carry out such a large-scale attack without running into obstacles, even if they had access to employee- or support-only tools. Especially as Twitter itself claimed at the time that “We are continuing to investigate and are taking steps to prevent this from happening again.” Perhaps the ‘steps’ were only taken to protect Trump’s account in particular?

The two-man rule

Separation of duties is a well-known security control that requires multiple people working together to perform a particularly sensitive task. In the military world, it has names such as “the two-person concept”. This approach protects against insider attacks by a single individual (which entails the vast majority of insider attacks) by default; it can be extended with other techniques to protect against potential collusion, too.

In the software world, separation of duties is supported via two main controls:

- Access control techniques: In general, the ‘superuser’ approach should be avoided, and tasks should be distributed between different levels of users, avoiding overlap (e.g. a database administrator should only have access to database maintenance functionality). Customer service accounts should have the tools necessary to do their job, but they should not be able to e.g. take over accounts for themselves without confirmation from a supervisor.

- Audit trail and anomaly detection: Logging any kind of dangerous activity in detail for later investigation. Raising alarms and (temporarily) locking accounts when detecting abnormal usage patterns (e.g. a low-level support account changing ownership of multiple accounts).

We don’t know what controls were applied to Twitter’s employee admin panels that were compromised via social engineering – but they were definitely insufficient in the end.

Twitter verified (‘blue checkmark’) accounts are handed out on a case by case basis to ‘authentic accounts of public interests’, which makes them valuable targets. Modifying ownership of (or posting tweets on behalf of) these accounts should be raising red flags and require some level of supervision, confirmation by a higher-level account, or perhaps even a time lock – while of course notifying admin accounts of the activity.

On the other hand, the system should be able to detect support personnel engaging in anomalous activity patterns, as mentioned above. Once detected, it should alert the security team to review these activities, and temporarily suspend the support account(s) in question.

Beyond Twitter: What can we do about it?

The question is not only “How is your organization prepared to handle an insider attack?” It is also if the products or services you are providing to your clients are appropriately prepared for similar situations.

First of all, we are all humans, susceptible to social engineering. It’s always a good idea to put in place appropriate company-level procedures. But no such measure is effective against social engineering unless education is in place so that employees are aware of the common tricks. As an additional control, many companies also set up red teams these days, who continuously challenge the personnel, thus testing their preparedness.

But human aspects are just one side of the coin. Developers should build systems to provide the most appropriate protections that are prepared for users making mistakes – simply because they will, no matter what we do. Access control does not seem to be rocket science. But there are many pitfalls if one does not deeply understand all aspects of it. Just think about separation of privilege, two factor authentication and all associated challenges (such as SIM swap), or all the best practices related to password management and authentication. Developers creating computer systems can be easily lost in all this without having the appropriate skills and internalizing proper approaches.

Logging and audit trails are also important when it comes to incident management. It’s not only about forensics, it’s also about deterrence. If potentially malicious users (insiders or not) know that robust audit trails are in place, they’ll think twice before engaging in malevolent activities.

As it happens, both of these issues are in the OWASP Top 10: A5 (Broken Access Control) and A10 (Insufficient Logging & Monitoring), respectively.

Best practices are out there. We just have to learn to listen and follow them.

We can help you avoid these pitfalls by teaching your developers about robust design and implementation of access control measures and logging systems. Check out our course catalog!