SQL injection: is it a solved problem?

SQL injection as well as its protection techniques have not changed much over the last 20 years. Is it still relevant?

The concept of SQL injection is well-known at this point. There is a popular XKCD comic about it, which in turn inspired a dedicated Bobby Tables website. People have even been making jokey company names and license plates with exploit strings.

Such a level of awareness and recognition surely means the vulnerability is no longer relevant, right?

From MSSQL piggybacking to the #1 spot

SQL injection was first mentioned (as ‘piggy-backing SQL commands’) in 1998 in the Phrack hacker magazine. Like other injection vulnerabilities, SQL injection is enabled by the programmer making a fundamental mistake – in this case, mixing up the nature of data and code. Specifically, input from the user (data) is inserted into a SQL query (code) – if the user is malicious, they can provide carefully structured input that changes the code being executed. In case of SQL, this can mean something as simple as returning all records instead of applying a filter, but it can also potentially modify, insert, or even delete elements from elsewhere in the database. In the worst case, it can even lead to remote code execution on the server.

SQL injection was so prevalent it quickly became a representative of injection vulnerabilities. As a whole, ‘Injection’ entered the OWASP Top Ten in 2004 at #6, climbed to #1 in 2007, and has been holding on to that position ever since.

A game of \’cat\’ and 'mouse%40%230039%3B

As with many other vulnerabilities, SQL injection attack techniques and defense measures constantly evolved parallel to each other in a cat-and-mouse game.

The original mitigation in the Phrack article suggested quoting strings and escaping quotes. This was implemented into many APIs at the time, such as mysql_escape_string() in PHP. Another attack to defeat this kind of protection abused how data is translated across certain multi-byte character encodings, such as GBK and UTF-8. And while the mysql_real_escape_string() function was resilient to this attack, it had several other problems. For one, escaping functions always use a built-in list of ‘evil’ characters that need to be escaped. However, the attacker may be able to perform an injection that does not require quotes, like when targeting a column name or numeric field, rendering these defenses useless. The attacker may also use hex string encoding to hide quotes.

Blacklisting was another typical solution that is still used today by web application firewalls and similar products. These simply forbid certain characters from getting through; however, with clever use of encoding tricks and SQL functions, an attacker can get around many of these protections easily. OWASP has some examples of evasion techniques here.

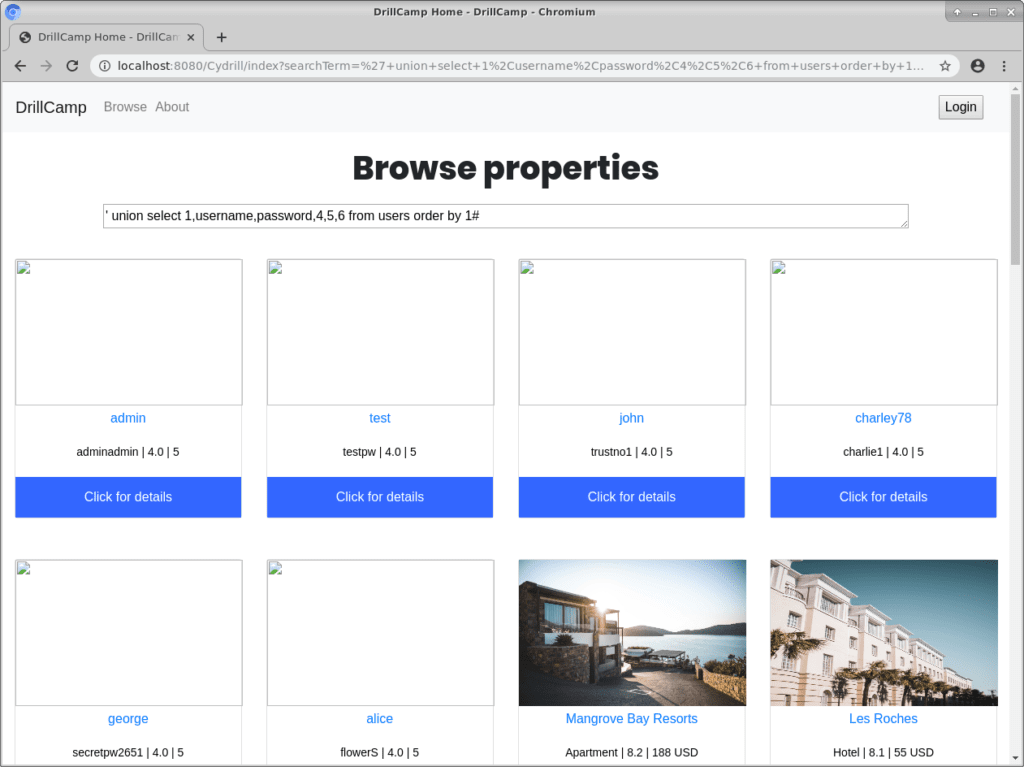

Of course, with such a well-known vulnerability type – that is usually exploited in a very similar way, with only minor differences based on DBMS and platform – automated detection and exploitation was also inevitable. Today there are numerous tools that can automatically find and exploit SQL injection vulnerabilities, such as sqlmap. Detecting SQL injection in source code is also fairly simple, as it always follows a pattern of inserting a user-provided string directly into a SQL query string.

As SQL injection stems from a conceptual mistake by the programmer by mixing data and code, the correct solution has always been there. Basically, separate the SQL query from user input and use a secure API to bind user input to appropriate fields within the query. Prepared statements or parameterized queries – originally created to improve SQL performance with repeated queries – can be used to realize this. As these techniques pre-compile the (static) statement and bind the user variables to the query, they can prevent the SQL injection problem entirely. No matter what kind of tricky string the attacker tries to send to the server, it will just be processed as data within the statement.

The good guys have beaten SQL injection – what now?

With such a silver bullet solution on hand, one would expect SQL injection to be a problem of the past… unfortunately, that has not been the case.

This site has been keeping track of PHP and MySQL-related questions and answers posted on Stack Overflow that contained code fragments with potential SQL injections. The most striking outcome is that the percentage of Q&As with potentially vulnerable code seems roughly constant at around 48-50% between 2008 and 2018 (with minor fluctuations), despite a significant evolution in protection measures! Searching NVD has similar results – SQL injection has been steadily making up 3-4% of all vulnerabilities since 2014 (with 2016 as an outlier). While it will never be as huge as it was during the late 2000s, it isn’t going away any time soon.

If anything, this highlights that no matter how ‘solved’ a particular security issue may look at first glance, it will continue to be a problem for a very long time unless it is literally made impossible for programmers to make the mistake in the first place.

SQL injection – and injection problems in general – is a very important topic; we cover it in our courses. Our material discusses state-of-the-art SQL injection attack techniques and tools as well as its relationship to newer ‘NoSQL’ technologies such as Hibernate, MongoDB, DynamoDB, and CosmosDB. More importantly, we cover the various protection techniques available to developers in a variety of programming languages and platforms.